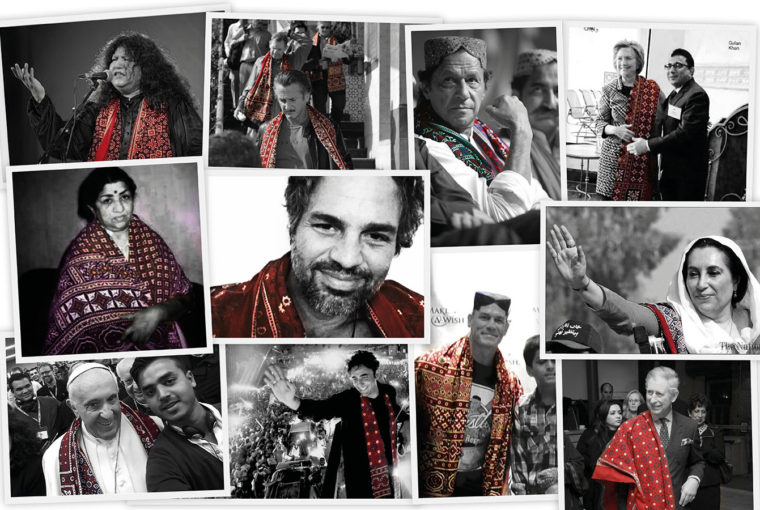

When in Sindh, don an Ajrak.

That is how it works. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a peasant or a prince, everyone wears it. Some wear it as a mark of belonging, others as a nod of respect to the ancient land of its origin. A tradition that started somewhere during the times of the Moenjodaro civilisation, this unique shawl has truly stood the

test of time. Who makes them and how? Our favourite explorer, Madeeha Syed makes a trip to the tiny village of Bhit Shah in interior Sindh and reveals the age-old techniques and time-honoured methods used, here in a tell-all.

When IN SINDH…

It was one of the hottest days of the year when we decided to go on a road trip to interior Sindh. In Pakistan, the month of May is absolutely brutal.

To escape the heat, most people prefer going up country to the mountains where the altitude and the glacial breeze keeps things kind of cool. Travelling in the south is usually reserved for the winter months – from October till March. In the summer the temperature can reach up to the late 40s. You can bake a roti on a rock outside in that heat.

My travel companions this time around included a rock and roll photographer, Wolfgang Burat from Germany. He’s photographed acts such as Nick Cave, Freddy Mercury, Sade, James Brown, Chaka Khan, Alex Chilton etc. There was also Markus, who teaches at a local university and is a journalist in a ‘legendary’ magazine that focused on counter cultures in Germany that Burat had founded, and Waqar J Khan, who is a designer that uses indigenous Sindhi craft and design in his clothes. The culture of Sindh, Sufi mysticism and German music – it was the perfect combination for a trip.

The heat wasn’t going to stop devotees from going to the urs of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar which was going to take place at Sehwan that weekend in May. People from around the country were converging to the Sufi saint’s shrine. We crossed several buses carrying pilgrims that way – who were going to offer their respects and spend the weekend seeking the blessings of the saint, engaging in song and dance to the sound of the music played by musicians who’ve been playing at Sehwan for generations.

But the heat doesn’t care whether you are on a spiritual tour or not. Over 12 people died of a heatstroke that weekend and as we were making our way, we were strongly advised not to go. And so, we went for Plan B: Bhit Shah. Playing instruments and singing at shrines is not the only tradition among some families in this Sufi belt of Sindh; the families of Bhit Shah are known for being the makers of the Sindhi Ajrak [shawl with an indigenous pattern].

Once in the area, on a narrow, easy-to-miss road if you aren’t watching out for the turn from the main highway, we came across a junction – one road led to the Sufi University of Sindh and the other, to the craftsmen we had come to see. You cross a few nondescript shops selling traditional Sindhi garments until you come across the plots allotted by the government for the preservation of this craft. Families both work and live on these plots. What sets them apart are the stunning, vibrant colours of their clothes – from bold, bright purples, pinks, yellows, red to green, blue and turquoise. Like birds of paradise (minus the pomp) they stand out in an otherwise brown and muted environment. It’s hard to miss.

For Ghulam Nabi Soomro, 40, this has been a family tradition for as long as he can remember. “This goes back generations,” he says ushering us into the cool refuge of his home and offering us some salty lassi (a watered yogurt based drink mainly used for its cooling effect). “My father did it, he learned from my grandfather, he from my great grandfather and so on… going back to a little over 300 years.” Ghulam Nabi oversees the operations on his lot. He’s got a head full of pepper-grey hair and a weathered face that makes him look older than his eyes. And he looks very amused at our fascination with his family’s craft.

THE MAKING OF AJRAK

There is a vat of dye being cooked above a brick-and-clay oven. The fuel? Firewood. Nabi says that alternative forms of fuel are not only more expensive, since it takes many hours to cook the dye until it’s ready, but they also don’t produce the same results. The dye being cooked is a deep red for the Ajraks and other traditional Sindhi block-printed garments being prepared. Some have been spread out to dry.

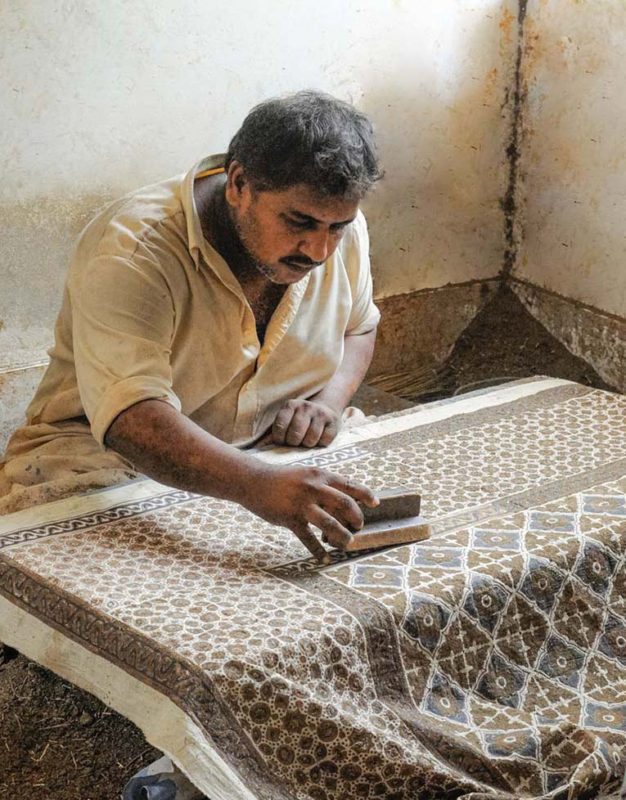

Workers in one of the rooms are using old wooden blocks, dipping them in dye and then carefully printing them on the Ajraks with an indigenous design that goes back to the ancient Moenjodaro civilisation! It’s a tedious task that demands precision. “The design on the Ajraks, on our clothes, all of it comes from there,” Nabi explains. “Some of these blocks are generations old and have been in the family for a long time. The design itself is over 5,000 years old.”

What’s more fascinating is the ingredients. “The dyes are 100 percent organic,” says Nabi. “They’re vegetable dyes. We use eucalyptus, pomegranate, mehndi [henna], old iron and for Ajraks we’ll use goondh [Tragacanth gum], turmeric, lemons etc.” But the king of all dyes here is the indigo.

The ‘blue gold’ of Sindh, the indigo plant from which the seeds for the dye come from, used to grow wild on the banks of the Indus River. No one knows why it went into decline this past century. It went extinct in its natural habitat until efforts were made by the WWF. Goth Sudhar Sangat (an NGO) started cultivating the indigo plant in Nawabshah and Matiari. The scarcity of indigo is what makes the indigo dye used for the Ajraks and other garments in Bhit Shah, extra special.

While all of the other dyes are cooked in vats and left to cool in the open after they are used, the indigo dye is stored carefully in an underground clay container of sorts and covered with a cap. The elder in Nabi’s group himself chooses to open the container and carefully dip cloth that has been block-printed by workers in another room completely into the vat. Excess dye is then squeezed out and back into the container. The cloth, now almost completed Ajrak, is then straightened and set out to dry under the baking sun.

The fact that most of the people in the lot gather around to watch just this part of the printing/dyeing process gives it a distinctive, ceremonial air.

Another special thing that happens only in Nabi’s printing/dyeing plot is the employment of the original, traditional technique of using a mix of fuller’s earth (a clay material) and dung printed on Ajraks to protect the previously-printed dye from being coloured over when the cloth is dipped in the main red or indigo dye. We go into a room where one printer, Mumtaz Taheen (35-years-old), works alone. He prints with the dung and then sprinkles on fuller’s earth before shaking what doesn’t stick off the cloth.

“He’s the only person that I know of that still uses this technique,” says Nabi. “Everyone else has stopped.” Why? “Because of the smell,” laughs Nabi, “Mushkil kaam hai” [It’s difficult work]. It’s true, there is a distinct smell of dung, although it’s not as bad as one would’ve thought. What do the others do? “They use chawal ka chilka [rice husks]. But that causes severe irritation to the skin. It’s not good for your health. It ruins your hands,” he explains as we step out to go into the room where he stocks the finished product.

Deviating a little from the traditional cotton, Nabi’s lot also prints indigenous Sindhi designs using organic, vegetable dyes on silk scarves, shawls and fabric meant for tailoring traditional tunics. He’s proud of the fact that several big-name clothing brands and designers all source their fabric and prints from him. He doesn’t seem to mind that they don’t credit him or Bhit Shah for it. For those interested in getting these from the source, technology and courier services have provided arims, who stopped by on their way to Sehwan, outside.

IN THE LAND OF LAL SHAHBAZ QALANDER

There was an air of festivity in Sehwan. You could hear dhol wallas [local drummers] going at it and people dancing on almost every street.

As we were planning to leave, a crowd gathered just outside Nabi’s lot, where a short while ago, volunteers baked rotis and doled out food for the pilgrims stopping by. In the middle of the crowd, a few people had started to dance to the beat of the dhol being played next to them. Little by little, more and more people joined. The moment they saw us approach, they extended their ‘performance’ a little. It was heartening to see people celebrate and enjoy themselves, just for the heck of it.

With fewer international tourists, you sometimes attract attention when you travel with foreigners. People especially want to get their photos taken with them. Markus, who’s been in the country for several years now and considers Pakistan his home, is used to the attention and happily obliged. “I get so much love here,” he laughed later on.

As a parting note, here’s a small tip. A must-do when leaving Sehwan is to have chai from a dhaba (food joint) at the highway. Ask anyone for the buffalo ‘bara’ and it’s right next to it. The milk that they use is fresh – sometimes just an hour or two old. The chai, absolutely divine.