It’s only a couple of hours from Karachi and not on anyone’s ‘top destination’ list, but for journalist and award-winning documentary filmmaker, Madeeha Syed visiting the shipbreaking yard at Gadani, Balochistan is nothing short of a great adventure.

My first trip to Gadani was when I was hosting a Portuguese backpacker who had previously travelled to over 170 countries in the world. This was also the first time I’d undertake a long road trip in my tiny car driving all by myself. Since then, I’ve made numerous trips: I’ve taken a couple of Spanish architects and also filmed a documentary short called Graveyards for Giants, that I won a small award for and which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. It takes roughly two to three hours from the center of Karachi to get to Gadani.

There’s a sharp turn on the left leading to the yards long before you get on the Makran Coastal Highway. It’s easy to miss which is why you have to keep an eye out for it. The road stretches for almost another kilometre before you finally get a glimpse of the giants — massive ships that tower several stories high and anywhere 900-1,200feet long — out of the ocean and right in front of you.

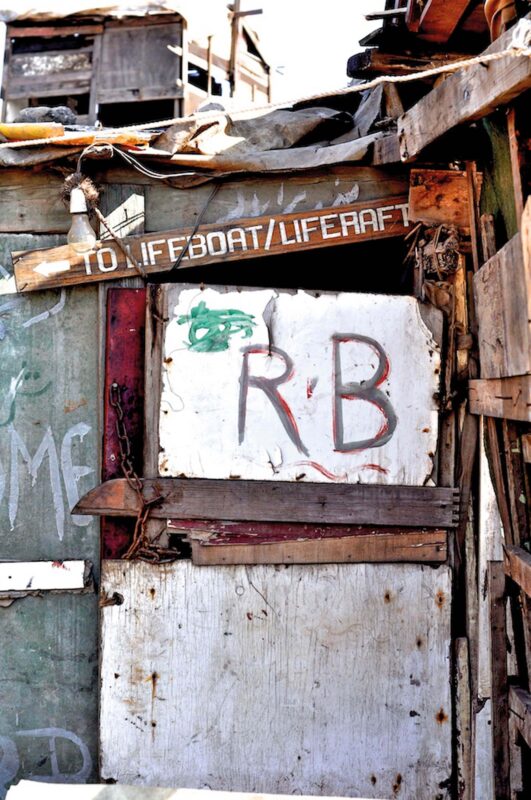

The workers — mostly Pashtun and Balochi — lead a nomadic lifestyle. Leaving their homes, often lush green valleys, to spend 10-11 months a year in a brown barren land constantly faced with the deep blue sea, isn’t easy. But it pays well. The workers have strong unions, get life insurance (their jobs are high risk, there are anywhere between two-four deaths per month, mostly because of a lack of secure attachments or inexperience), medical and their living expenses are almost none. They live in make-shift shacks opposite the lots. But what’s interesting about them is that they’ve used pieces from dismantled ships to build their tiny homes — you’ll find signs in foreign languages and even boards with “BR” (Bakhair Ragulay – Welcome) fixed on those tiny huts.

Spend a few hours at the lots and you’ll see how the workers break a ship down — piece by piece, using very rudimentary technology and machinery, through sheer man power. You see them gathered over massive propellers half in the water, moving because they’re being pushed by the wind, and a group of men gathered over it, getting it under control and trying to breaking it down. It’s hard not hear the Titanic soundtrack in your head at this point.

A once-in-a-lifetime experience is being lucky enough to watch a ship being beached. Sold at auctions in the UK, these ships cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, so it’s very important to get a captain with experience in beaching ships. One wrong move and you’ve destroyed your investment.

The owner of the lots come down for this day and all of the workers gather on the beach, ready to move. The ship is at a distance of about 10-15 nautical miles and clearly visible from the coastline. Before anything can begin, everyone gathers for a joint prayer. Then the manager of the lot, who is also chief navigator, communicates with the captain via a wireless phone, instructing him on how to align the ship so it is perfectly straight. Once that’s done, things begin to move very fast.

The captain moves the ship forward, full steam ahead, and rams it into straight into the beach. If the beaching is successful, the ship won’t fall on either side (literally). The workers can be seen running around the yard securing lines to keep the ship in place. Once that’s done, the tricky (fun and exciting) part the beaching process is over. The owner goes back to his office. At some point, you’ll see a uniformed figure in white disembarking from the ship on a rope ladder — that is the captain. Later, workers will use similar ladders to climb to the top, or use the stairs inside the ships to get to where they want to go.

Close your eyes and you can sense the sun, sand, sea and steel around you. The salty air, the smell and the metal clanking make you feel like you’re in an otherworldly place. Perhaps this is what those who designed some of the earliest large ships felt like when they walked into the garages where such giants were, at some point, built by mostly by hand and rudimentary technology. We’ve come a long way since then.