Travel enthusiast Aleemah Noon travels to the land of her ancestors in Southern Punjab, and delves into the history of Fort Munro, once a stronghold for powerful Baloch tribes that eventually became a British outpost and the summer headquarters for the administration of the Raj. She discovers a town steeped in the mystery and romanticism of the past, yet with a will to reinvent itself for the future.

Being consumed by wanderlust can lead you to many places for a ‘holiday’ but it’s not often that your soul cultivates in tandem with your journey. My trip to Fort Monro was of that rare variety. The canyon-like cliffs of the Anari Pahari (Pomegranate Hill) where the clouds encompassed you, the rocky hillside strewn with sparse exotic greenery, the layered hills that blurred like a sepia rainbow in the horizon – all had an enigmatic quality. The town had the ingredients for a real-life Pocahontas setting – the voices of the mountains, the colours of the wind, the wise old tree and the feeling of walking in the footsteps of a stranger to uncover secrets from the past.

Fort Munro is a classic colonial hill station – but with a depth and mystery that doesn’t exist in the now-congested Murree. An uplifting adventure begins as soon as you set out towards the undulating Leghari territory (aka Tuman Leghari) – a mix of beauty, history, culture and cool weather. It is situated in Southern Punjab – a part of the Sulaiman Range, along an ideal route where it touches upon all provinces and provides a safe gateway into Balochistan. As a significant trade route, the road leading to Fort Monro is lined with hundreds of trucks transporting fruit, livestock and coal amongst other things, one direction or the other. The Japanese have recently started an astonishing project whereby they have undertaken the construction of 8 steel bridges in the measly span of 30 or so kilometres along this road, adding to the heavy traffic.

I started this trip on a whim; to break away from Lahore’s relentless summer. A short city break ended up yielding experiences that made me grow exponentially. The long Daewoo bus ride and the short cab hops across the changing landscape of Southern Punjab took me on a journey where I rediscovered my maternal roots and of course eventually, the hidden hill station of Fort Munro.

Two hours from DG Khan, we spent the afternoon in Nawa Shehr, next to Choti, where my late grandfather’s family received us with love, delicious food and ethnic gifts, including the famous Choti embroidered suits. I was transported to another time period, emerging into a part of my history that I had no interest in before my chance arrival there.

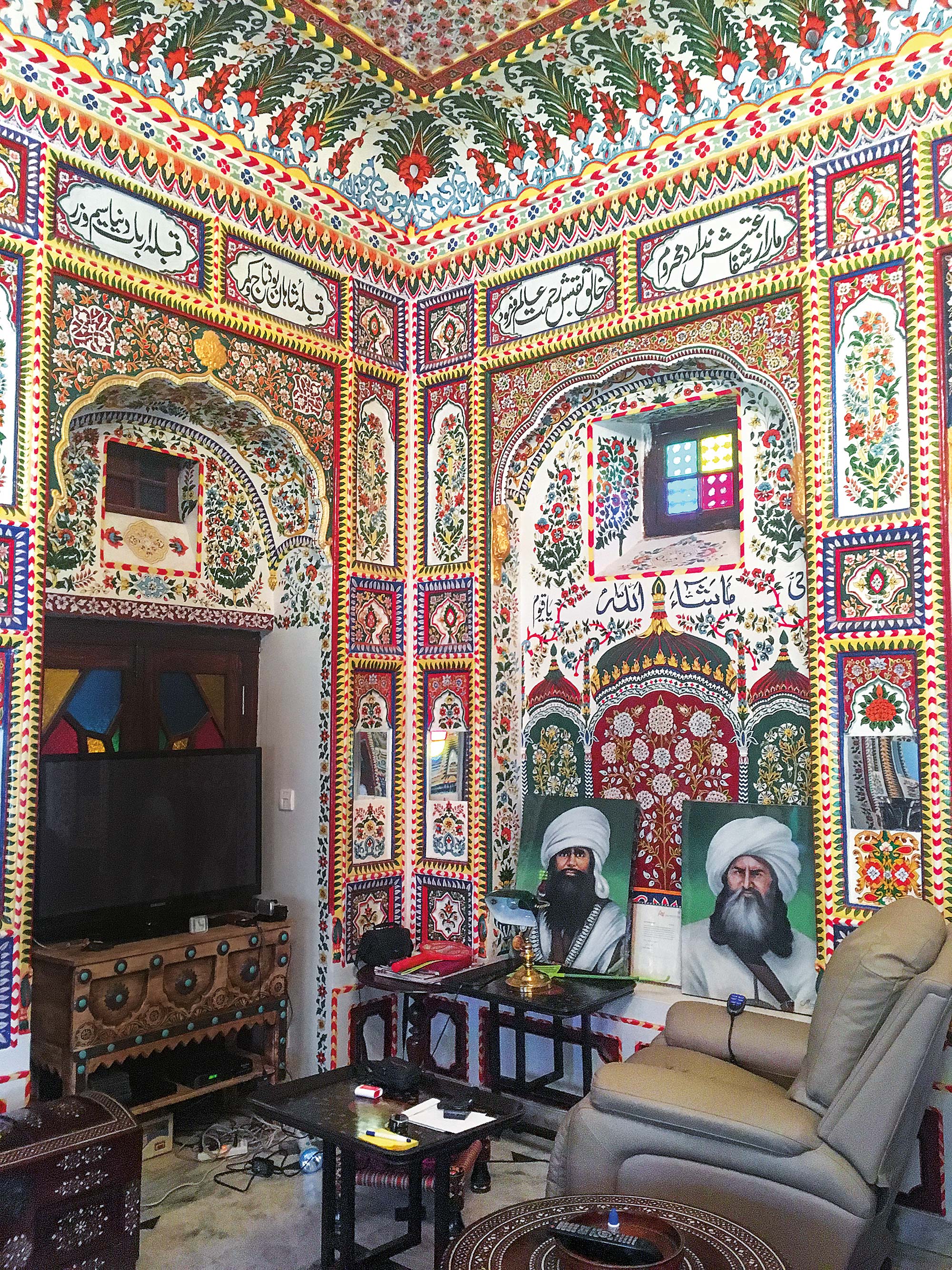

We then set out towards Fort Munro with another quick but interesting stop at the Sakhi Sarwar shrine. The locals have it that thousands of years ago, this was a Hindu shrine where barren couples would come for blessings. Over time, the region was benighted. In the 13th century, the saint Sakhi Sarwar arrived to enlighten the people and eventually died there. There is much folklore surrounding his life but what’s indisputable is that he was called sakhi (generous) for his generosity and affection to all people and animals. Incredibly, till today people of all religions visit the Sang Mela – the annual urs or death anniversary of their beloved saint. Visiting this shrine is a unique experience: it has an upbeat rather than a solemn vibe, the Mughal art and architecture with hints of colonial redesigning providing a striking visual experience. A cave-like room to the right of the tomb holds two stalls where I got my head rattled with heavy chains and then oiled as blessings in exchange for money; the walls of this room were covered with murals of the saint and his devotees.

We finally arrived at our destination after passing through winding roads and absorbing scenery. We were staying at the late ex-president Farooq Leghari’s home situated at the top of a hill, hosted by his son Awais Leghari, his wife Arjumand and their son. Their unassuming hospitality and genuine love for the region was refreshing.

Over a delicious homemade meal, Awais recounted the history of Fort Munro and its tribes. The various tribes, including the Gurchani, Khosas, Kesrani, Khetrans, Buzdars, and Mazaris, had a strong tribal code in the form of a jirga (tribal council). The jirga meetings of the tribes from the DG Khan District in the north all the way to old Dera Ismail along the Balochistan border would be held here, as a result of which Fort Munro gained regional importance. The original jirga hall no longer exists but a newer structure stands at the same spot. The British designated pieces of land around the hall to the sardars or chiefs to be able to host their tribes during the times the jirga was in session; they would pitch their tents and there would be food and entertainment. However, even the sardars would live in utmost simplicity as there was a great deal of poverty in the region. The sardars’ purpose was selfless – to give protection to their tribes.

Apart from being the head of the jirga, the Leghari tribe was greatly respected by the others because they had invested in the construction of an inundation canal that led them to great economic prosperity. Their progressive mindset also lent them greater political influence in the area as they believed in education and equal rights for women. In fact, Sir Jamal Khan Leghari set an example by giving the women of his family all inheritance rights including property and weaponry.

Fort Munro was the last tribal stronghold that the British were able to encroach into as part of their ‘Forward Policy,’ partially through the Leghari family. Henceforth, it became a British outpost and the summer headquarters for the administration; its officers were permanently positioned here and one can clearly see and feel the strong colonial influence throughout the hill and the valley of Khar.

We were lucky to be given a personalized tour of the area by Asfandyar Janjua, the DG of Fort Munro Development Authority (FMDA). He took us to the Officer’s Hill at 6500 feet, which was naturally emblematic of the British Raj. Built possibly in the late 1800s, the residences on the Officer’s Hill, namely Munro House, Sandeman House (PA House) and the Commissioner House, were the archetype of colonial architecture, featuring high ceilings with wooden beams, huge fireplaces, sandstone-coloured walls, stained glass windows and roshandaans (moucharabieh), and cypress-lined gardens with grand views.

Walking inside the PA House, history stood still as our eyes fixed on an antique billiards table with all its accessories intact and coated in dust, the balls boxed up inside a glass cabinet, and an empty spectators’ bench. The fort itself or what’s left of it was more of a sandstone watchtower. The Christian graveyard was intriguing as the epitaphs on the tombstones told stories of those who had once lived here; it was depressing to see the graves of the 8-month old baby James Frederick and 5-day old baby Walter amongst other teens and young ones.

In the evening, Awais and his family took us for a picnic across their lands to Moon View Point where I sat at the edge of a cliff and practiced my shooting skills with a Kalashnikov. We drank delicious hot tea and had sittas (corn) while overlooking the spectacular view. Like a hidden treasure, a revered saint by the name of Daru Pir lives a long trek down that hill. I was curious to visit him but sadly didn’t have the time. On the way back we crossed a 500-year-old olive tree with huge gnarled roots, which according to popular legend makes your wishes come true!

The famous Balochi sajji was on the menu for dinner at the Legharis’ on our last night, it was the most tender meat with no added flavours except for salt. Over dinner, we discussed the Fort Monro Development Authority’s promising vision for a well-planned and clean holiday town. The most exciting projects comprised of family-designated campsites and parks; adventure clubs that would offer activities like ziplining and parasailing; revamping of the colonial-era tennis courts and a sports complex that was built by Farooq Leghari when he was president; forestation and creation of trekking trails. The night grew chilly as we sat on the Bhutto Terrace enjoying the gusty wind that whistled through the pines. And that ended our fabulous stay in Fort Munro.

The drive back to Lahore was long and hectic, but we still made a quick pit stop in Choti at Jaffer Leghari’s fascinating fortress/home with exquisite murals and stained glasswork. Fascinatingly, it houses a small museum with authentic Indus Valley artefacts. I took a quick skim through it all, but I can’t wait to be back to explore that on its own.