As the Aga Khan Cultural Services Pakistan enters its third decade of operations in the country, the organization’s mission to improve socio-economic conditions of rural and urban communities by leveraging the transformative power of cultural heritage has only strengthened. With numerous award-winning projects in the high valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan under its belt, AKCSP is currently involved in restoration works within Lahore’s ancient Walled City.

Constructed in 1635 by the then Governor of Lahore, Ilam-ud-din Ansari, the Shahi Hammam stands as the last remaining hammam (built during the Mughal era) in Lahore’s Old City, close to the Delhi Gate. However, with the collapse of the Mughal Empire in the 18th century, the once grand and picturesque hammam slowly fell into damage and ruin under the British rule.

But in 2015, after a painstaking two-year restoration process, the

Shahi Hammam was unveiled for public viewing. Carried out by the Aga Khan Cultural Services Pakistan (AKCSP) in collaboration with the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) with generous funding from the Norwegian government, the ambitious project was no easy feat. Decades of damage had chiselled away into the structure. In fact, during the restoration process, it was found that significant parts of the hammam had been destroyed for the Delhi Gate’s renovation during the 1860s.

Exactly one year after the AKCSP’s renovation of the building, in 2016, the project bagged a UNESCO Award for bringing the hammam back to its former grandeur and glory.

“Our focus from day one has always been development through cultural restoration,” states Wajahat Ali, the Manager of Design and Conservation at the AKCSP in Lahore. “We believe in community-based conservation where we engage with the community for our restoration projects.”

Aga Khan Cultural Service Pakistan (AKCSP) is the Pakistan arm of the Historic Cities Support Programme (HCSP) of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) based in Geneva. The programme has been involved in urban regeneration projects in nine different settings in the Islamic world: Afghanistan, Bosnia-Herzogovina, Egypt, India, Mali, Pakistan, Syria, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Zanzibar through the restoration of historic structures, the creation and rehabilitation of public spaces, parks and gardens and support for community-based planning and upgrading projects.

Since its inception, the AKCSP’s efforts have gone a long way in the preservation of Pakistani art, culture and heritage, paving the way for future generations to both enjoy and learn from.

Apart from its extensive work in Lahore since 2007, the AKCSP has also worked closely with Gilgit-Baltistan’s tourism and culture department on four projects in the area, namely the Baltit Fort (which was one of the AKCSP’s first projects in the 90s that was eventually completed in 1996, and went on to win the UNESCO Award of Excellence in 2004), the Shigar Fort, the Khaplu Palace (that received an Award of Distinction by UNESCO in 2013) and the Altit Fort (that also received praise from UNESCO in 2011 with an Award of Distinction).

“Did you know the economy of Gilgit-Baltistan runs on the AKCSP’s four projects? They have approximately 50,000 tourists on an annual basis,” Ali says. “This year the expected footfall is one million; there has been an enormous increase in employment in the area.”

For Ali, having been in the field for sixteen years and counting, cultural heritage can be used as a powerful development tool to address poverty and unemployment. “Take a look at Hunza,” he goes on to explain. “Thanks to travel and tourism they’re thriving.”

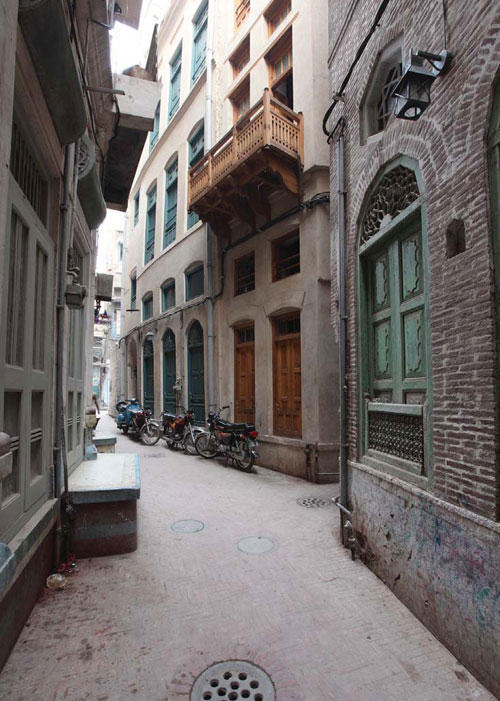

Having been operating in Lahore since 2007, Ali reveals that the AKCSP has been heavily involved in the strategic planning of the Walled City, in addition to the conservation of landmark projects, such as the Gali Surjan Singh (a residential area located inside Delhi Gate), and the Wazir Khan Mosque, apart from others.

“Conservation is much more than the drawings,” Ali says. “We have archaeologists, chemists and microbiologists on board with us too! Also, you have to understand, in our field, time is a given – conservation is not an overnight process. Conservation must have impact, and most importantly, it must be long-lasting.”

But in a country that has never seen consistent socio-economic stability, how does one make the public aware of the importance of their heritage, and most importantly, their identity?

Take a tour down to the Lahore Fort, and you’ll be greeted with filth, litter and pen markings scrawled across walls. And that’s just one example.

However, Ali believes that when change and development is tangible, that’s when there will be a shift in society for the respect and appreciation for Pakistan’s cultural identity.

“People need to see one project… just one demonstrative project,” Ali goes on to say. “Everyone, including the government needs physical proof and evidence of a project that has been refurbished – it really is the only way to make our people value their heritage.”

Having enjoyed a booming travel industry in the 60s and the 70s, it is time Pakistan reclaimed its space in the sphere of both local and foreign tourism. Besides, initiating and then cultivating a connection with one’s art, literature, and history truly does go a long way in inculcating a spirit of patriotism to one’s rich and diverse homeland.