Leading journalist and media producer Fifi Haroon recently met notable film director Gurinder Chadha and lead actor Huma Qureshi at the hipster Soho Hotel in London before the release of their latest film, Viceroy’s House. Based on the events of 1947 as the British colonizers prepared to leave the once mighty India, to then be divided between Muslim and Hindu majority areas as two separate countries, the movie has incited much debate amongst the previously-colonized natives after its recent release, specially amongst the Muslims of Pakistan. Here the ladies from across the border try to set the record straight as they discuss the motion picture at great length.

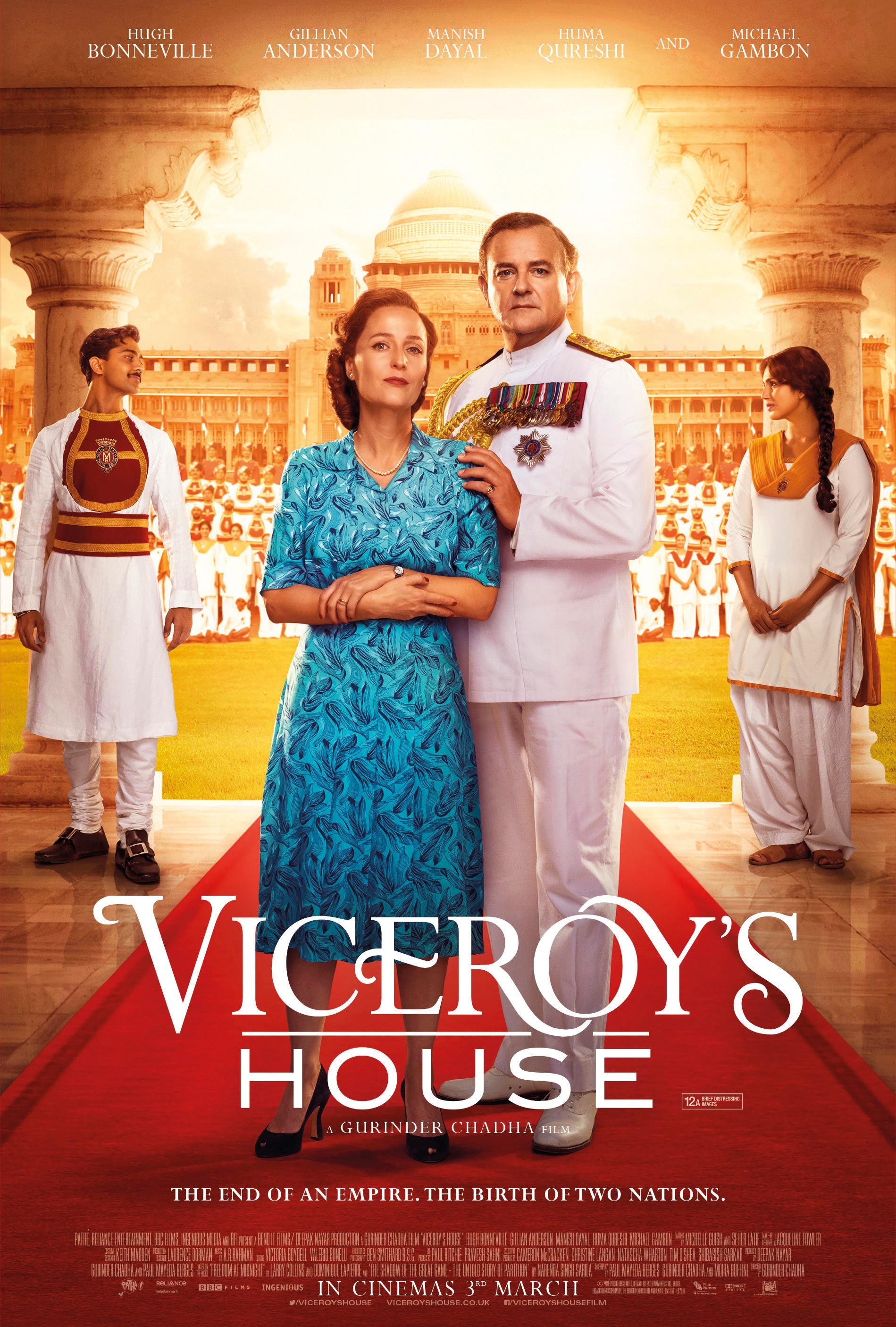

A film on the traumatic and bloody partition of the Indian subcontinent was never going to satisfy everybody, but equally perhaps it would be telling to see who director Gurinder Chadha’s epic saga Viceroy’s House does satisfy and whom it may be bound to upset. With a stellar cast including Hugh Bonneville, Gillian Anderson, Huma Qureshi and the late Om Puri, the film has opened to cinema audiences in the UK eliciting largely favourable 3-star reviews for its epic proportions and sudsy storytelling but also an undiluted rant from writer/activist Fatima Bhutto in The Guardian, who rather scathingly termed it “a servile pantomime” from a “colonized imagination.”

The vast canvas of Viceroy’s House opens on the final year of the British Raj in India. It’s 1947 and the Mountbattens, flush with the success of Burma, have arrived in Delhi to oversee the messy, cumbersome task of setting an almost 200-year-old British colony free. As they move into the Viceroy’s home with their daughter Pammy, we are also introduced to a cast of locals who cook, clean, help dress their royal masters and form the underbelly of the mansion. More revealingly, the film is also the result of a very emotional personal journey for the director, who earlier directed the extremely likeable Bend it like Beckham in 2002. From the start of her career as a filmmaker, Chadha has prided herself on bringing a “uniquely British Asian perspective” to mainstream cinema; one which she tells me she upholds in this film but without quite explaining how.

As a Sikh whose grandparents lived in Jhelum and Rawalpindi and migrated to India when it fell on Pakistan’s side of the border, the director acknowledges that this emotionally fraught familial history seeded her passion for making the film. But it seems this personal trajectory also determined the political diorama that is Viceroy’s House. Partition has long been a primal wound for many Indians and indeed it would seem too for the film’s British Indian director but this aching feeling of being “wronged” or unwillingly siphoned tends to overlook that it led to freedom for Pakistan. Not only is the film’s narrative reductive when it posits Pakistan’s birth as behind-the-scene geopolitical deal-making between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Muhammed Ali Jinnah (played rakishly by Denzil Smith), it almost presents it as a last-minute irritant with no real roots in the soil. Chadha seems to think everything went belly up suddenly for India’s varying populations (“overnight people were ready to kill each other when they had been fine for ages,” her grandmother told her) and the empire’s “divide and rule” story we were fed in schools across the subcontinent is close to hogwash. She doesn’t openly say partition is the Muslim League’s “fault” in her interviews but the fact remains that in the film Pakistan is presented more as stolen land rather than a country which was fought for and achieved. And Chadha, who is well-meaning enough when I interview her, reveals no real understanding of how this incorrigibly colours Viceroy’s House’s political narrative, which is heavily borrowed from Narendra Singh Sarila’s 2009 book The Shadow of the Great Game: The Untold Story of India’s Partition.

On the flip side, Viceroy’s House is undoubtedly a sumptuous film and handsomely shot; the last sigh of the British empire in undivided India skilfully brought to life in the insulated grandeur of it’s last Viceroy’s House. It is also an enjoyable upstairs-downstairs Downton Abbey of a film; with the epic television serial’s pater Hugh Bonneville playing merely a variation of the Earl of Grantham as Lord Mountbatten. Far more convincing even if exaggeratedly mannered with constantly raised shoulders is Gillian Anderson (The X Files, The Fall) as Edwina Mountbatten, the memsahib who consoles her woebegone husband “Dickie” with: “This tragedy is not of your making.” In fact if there is anyone who is presented as almost faultless in the narrative logic of Viceroy’s House it is the amicable, khaki-wearing aristocratic duo who just want to do their best for this wonderful former colony as starving, bloodied migrants flood into refugee camps. Chadha completely glosses over Edwina’s documented affair with Jawaharlal Nehru and her voracious appetite for passionate extra-marital liaisons (18, by her daughter Pammy’s account) by saying it wasn’t relevant to her story. I would suggest it is actually fairly pertinent to a film that tries to unveil the hidden political navigations leading to a rather sloppy border demarcation in 1947, including forging a Pakistan oddly split into an east and west wing. But exit the bad Mountbattens we know so well and enter the do-gooder Mountbattens. To deify them to the extent this film does I feel goes well beyond the call of duty.

The lack of an admission of passion upstairs is matched by true romance downstairs in the form of the most familiar trope that could be conjured up. A Muslim girl (Huma Qureshi) and a Hindu boy (Manish Dayal) find their Montague-Capulet love is split asunder as a country heaves, stutters and finally descends into carnage and chaos.

I met director Gurinder Chadha and lead actor Huma Qureshi at the hipster Soho Hotel in London before the film’s release. Chadha had almost lost her voice after numerous interviews but was braving it for the cameras. Filmfare award nominated Huma Qureshi – known primarily for the two-part crime saga Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) and Desh Ishqiya (2014) – was in turn articulate, giggly, intelligent and warm.

HUMA QURESHI

After the success of Viceroy’s House do you feel your career will now take off in a more westerly direction?

That’s what everyone keeps telling me. I just did this film because I thought it was a great story that needed to be told and it’s a director I wanted to work with. Not necessarily because it’s a western film.

I suppose because of Priyanka Chopra making the trek to the big time and Deepika doing xXx: Return of Xander Cage there is a trend now where Bollywood actors seems to be looking at Hollywood.

All the best to them. I think they’re doing wonderfully well for themselves and for the country but I can’t really comment on how they are charting their careers. I can only speak for myself. I like to do films and scripts I believe in. They could be in any language – I’ve done regional films also because I thought the story was damn interesting.

What is it about a role that draws you in? What drew you into this particular role in Viceroy’s House or drew you towards your role in Gangs of Wasseypur or any other roles you’ve done?

I like to do films with a soul. And characters which have a point of view. I can think of 10,000 other things but to boil it down its important for my character to have a point of view. It could be right or it could be wrong. I could be playing a really grey or dark character but she should have a point of view.

Do you have to agree with that point of view?

No, as a person I may not agree with it at all. I may in fact detest it but that’s what makes it far more interesting as an actor. For example I play a sex worker in a film called Badlapur. Now I may not agree or identify with it at all but for me, for Huma as a person, it made me question a lot of things in my head. I had to really work out of my skin to play that character. Or it could be a role like Haseena from Gangs of Wasseypur where she’s married to a drug lord and she’s the daftest thing on the planet who’s just happy singing songs while her husband is butchering people. But for her, the love for her husband was supreme and that was her point of view. As an actor, it’s exciting when I genuinely get to be another person.

Did anyone in your family have memories of partition that they shared with you? Or memories of what they had been told because every generation re-writes history a little bit.

Thankfully my family didn’t experience the more brutal fallout of partition. My grandfather had a massive house in Nizamuddin in Delhi and when a lot of people started coming in from what is now Pakistan, he gave them a place to stay. So whole families were cramped into a room because that is what he could give them. My family’s stories from that era are more about what other people went through.

Your grandfather chose to stay in India?

Yes he chose to stay. But one of his sisters is married to a Pakistani and lives there.

So your aunt is a Pakistani?

My grand-aunt yes. My grandfather’s sister. My father runs a restaurant in Delhi and a few years ago a man came up and said to him, I’m your cousin. He had come from Pakistan for some work and was trying to track down his family tree. And then they spoke and turned out they were cousins who had never spoken. He was from that branch of the family that we had completely lost touch with. So there are many stories like that. My mother is a Kashmiri and Kashmir is quite a hotbed of discussion between India and Pakistan so we have a lot of conversations around that. My maternal family is still living in Kashmir, my khalas and cousins and everyone.

Do you go to Kashmir?

Very often but the last time I went there was three years ago. When my grandparents were alive we used to go there every year and spend up to a month because they were really old and couldn’t travel. We have great, amazing memories from that time.

You come from a really interesting background; a grandfather who chose to stay and a mother who is a Kashmiri. So there is your whole personal history connected to partition and also the history of your character Aliya. Do you think that your inclusion in the film validates the narrative of the film or do you feel you don’t need to agree with the narrative of a film you work in?

Wow! Does my inclusion validate the narrative from my side? I guess in a way it does. And I know I’ve just said to you that I don’t have to agree with the point of view of my character. However in this film I do. For me, I was not just making a film. While filming I was very much aware of the burden of history or the proof that one had to bear. For me if you take away all the political stuff, and the discussion of whether these new documents are true or not, the fact remains that this was a very human problem. Where people were asked to choose whether they wanted to stay or whether they wanted to leave their homes. It was not just a line drawn on a map or a piece of paper. It was a line drawn across people’s lives, hopes and ambitions. And it changed them forever.

The film’s version of why partition happened is a very contested one that will be problematic.

Of course it will. Depending on whether you’re Pakistani or Indian you will always feel that because you will have some sense of allegiance or loyalty. But it’s definitely not a film that is unsympathetic to Pakistan. A lot of films about partition do paint Pakistan in a slightly unflattering hue. I am saying at least we’ve tried not to make a jingoistic film. For me if you feel that what happened was not right, the carnage and the lives that were lost and for the madness that happened – if you just feel for that at some level, then our job as a film is done.

Om Puri played your father in the film. He worked in Pakistan as well and his co-stars here like Fahad Mustafa and Mehwish Hayat were full of praise for him.

Whenever I am asked to speak about him, I never make it to talking about his films because I get caught up just talking about the person he was. The first day I met him on Viceroy’s set I started calling him Abba. And he would always treat me like a daughter. I have so many wonderful stories about him. Like he’d pick up little toys for me. You know the inexpensive animal toys you find at airports. A toy horse or elephant. And I would feel so touched. I mean, who does this in today’s world?

You’ve had two big films released at the same time, the other being Jolly LLB with Akshay Kumar who is much older than you. Why is it that actors can progress to any age and yet have such young heroines cast opposite them? Why is it never the other way around?

It can be the other way around but see, the incidence of that is less in real life as well. I think cinema is a reflection of society. What you see in real life is what we show in films. Why hold cinema responsible for everything? If you take issue with something then let’s talk about changing it in society first and then cinema will follow suit.

Okay so forget about the older actors – what if you’re offered a film with Fawad Khan? He’s hot isn’t he?

I would love to do it. He’s very hot. And now I have gone on record saying it!

GURINDER CHADHA

How do you feel you have changed as a filmmaker from the days of Bend it like Beckham?

Actually my first film was Bhaji on the Beach…

Yes but I think it was Bend it like Beckham which made Gurinder Chadha a recognizable name at least in other parts of the world or in Pakistan where I saw it.

I’ve made films across many genres. I made a musical called Bride and Prejudice. I made a Hollywood film Angus, Thongs and Perfect Snogging. But this is my most ambitious film to date. I wanted to make a big historical epic in the style of a British Raj movie.

So when people say this is a very David Lean-esque film – which a lot of the reviews are saying – do you agree?

Definitely. Because it is epic in that sense. I wanted to paint on that kind of large canvas a film about our history. I think what I am consistent with and throughout my career and what I relentlessly try to show is a British Asian perspective. Every film I make is British and it is Asian.

Yet it is the Mountbattens who come out the cleanest in Viceroy’s House. Almost as angelic I would say. What was this need to show the Mountbattens in this righteous spotlight?

I don’t think they are the only ones. I think the Mountbattens have always been blamed in India for partition and I wanted to show that actually they were used. And they didn’t leave right away. There is a lot of archive footage of Edwina Mountbatten in various refugee camps, you know getting her hands dirty and getting involved in a way no other vicerine had till that point. I equally showed Jinnah talking about his vision for Pakistan. What he feels the country will represent for him and I think that’s a great statement he makes about Pakistan being a country open to all religions and friendly to all its neighbours. That’s something you never hear about. I also show how Gandhi was sidelined but Gandhi also has responsibility because he took a vow of silence on the day that the document was signed.

Why in particular did you choose these actors for these roles – Gillian Anderson and Hugh Bonneville to play the Mountbattens?

I really wanted it to seem like a period film. I had never made a period film and I wanted actors that felt like they could have lived in 1947. And I think these two actors for me really sold the period aspect of the film. Particularly in Gillian’s case, I feel she really took on Edwina in her mannerisms. She walked and talked completely like her.

Apart from an arched eyebrow from Lady Mountbatten there is very little reference to the grand affair that has been documented by history as the affair between Nehru and her. Why did you leave that out?

Because I really didn’t think that was the story. I wanted to tell the story of why my grandmother suffered during partition, not why these two might be having an affair. I referenced it in the sense that they are obviously close and they have a close relationship but I didn’t think there was any benefit of taking that story further to the story I wanted to tell. It was more important for me to show the love story downstairs as a metaphor for the whole of India. The Edwina-Nehru affair had nothing to do with the politics of partition.

But this love between a Muslim girl and a Hindu boy set against a political backdrop is a theme that has been played out time and time again. Don’t you think that was putting it a little too literally – seems a bit pat?

Could be, could be. That’s your opinion. A lot of people are moved by it. It’s not a traditional love story; they’ve already split up and he’s come back to chase her. And then they’re caught up in world events. It’s emblematic of how events upstairs affect the downstairs.